Research on the psychology of animal product consumption is rapidly expanding into new areas, including dairy, egg, and fish consumption, moving beyond just meat consumption. Maria Ioannidou has been at the forefront of this emerging research, with several recent articles published in Appetite and Food Quality and Preference. In this blog, we discuss her fascinating research, which provides a glimpse into the minds of vegetarians, pescatarians, and omnivores.

Can you briefly introduce yourself, Maria?

My name is Maria Ioannidou. I completed my PhD in 2024 in the area of social and moral psychology at the University of Bradford. Before that, my academic journey began with an honours degree in Psychology and Crime and an MSc in Psychology, both at the University of Bradford, followed by an MSc in Forensic Psychology at the University of York.

I’m currently the Graduate Student Representative for the PHAIR Society, and serve as events and conference co-organizer. Beyond academia, I am an animal rights activist, a cat and dog mother, and I take care of stray cats in Athens.

How is it possible that some people (pescatarians, vegetarians) can stop eating meat over concern for animal welfare while at the same time continue consuming other animal products, knowing this involves severe animal welfare issues?

You recently completed your PhD on the psychological factors that underpin animal product consumption. What inspired you to do this research?

I became vegan eight years ago after watching Dominion, a documentary that forever changed my life and my perspective on humanity. Following that, I engaged in various forms of animal activism. When I was pursuing an MSc in forensic psychology, I began to wonder, as many people before me: Why do we love some animals but eat others? After delving into the research literature on this topic, it all started to make sense as I recognized many of the justifications and psychological strategies that people use to feel more comfortable with meat consumption. For instance, I often heard the claim that animals don’t really suffer in the meat industry or that animals only have limited mental capacities to feel or suffer. Research has shown this is one way of how people convince themselves there are limited ethical issues with eating animals, enabling them to continue consuming meat. However, I also kept wondering about dairy, egg, and fish consumption, given that most research had been focusing on meat consumption.

Through my activism, I encountered various justifications for consuming dairy, eggs, and fish such as the misconception that dairy and egg production are part of the animals’ natural processes and don’t involve animal suffering. Coming from Greece, another striking example concerns people’s consumption patterns during the Greek-orthodox fasting period before Easter. Despite fasting entailing abstinence from animal products, many Greeks still eat fish during this period because they do not consider them animals.

These personal experiences and anecdotes suggested the use of cognitive dissonance strategies may not be limited to meat consumption but also apply to the consumption of other animal products. Given the lack of research on the psychology of dairy, egg, and fish consumption, I wanted to pursue a PhD to investigate these ideas.

A key question I wanted to address was: How is it possible that some people (pescatarians, vegetarians) can stop eating meat over concern for animal welfare while at the same time continue consuming other animal products, knowing this involves severe animal welfare issues?

In one of your articles “Feeling Morally Troubled about Meat, Dairy, Egg, and Fish Consumption” published in Appetite, you investigated the use of rationalizations and dissonance reduction strategies in a range of dietary groups based on survey data from hundreds of respondents, including omnivores, pescatarians, vegetarians, vegans, and flexitarians. What did you find?

As expected, meat consumers (omnivores and flexitarians) used rationalizations to justify their meat consumption, for instance, agreeing that humans need to eat meat to be healthy. They were also more likely to deny the suffering of animals killed for meat compared to meat abstainers (pescatarians, vegetarians, vegans).

Critically, the main new finding was that similar rationalizations and dissonance strategies were used by dairy and egg consumers, including vegetarians, to justify egg and dairy consumption, as well as by fish consumers, including pescatarians, to justify fish consumption. For instance, whereas vegetarians and pescatarians acknowledged the suffering of animals in the meat industry, they tended to deny the suffering of animals in the dairy and egg industry. Similarly, fish consumers used justifications to defend fish consumption (“humans need to eat fish for a healthy diet”) and were more likely to deny that fishes suffer when being raised and killed for fish production, compared to fish abstainers (vegans and vegetarians).

People perceive the intelligence, sentience, and moral worth of animals in a selective and self-serving way, motivated by their dietary behaviour.

Did you find any evidence that these dietary groups also differ in the way they perceive animals used for food? You investigated this further in your article “Minding Some Animals but Not Others”.

Yes, in that study, we presented participants with a list of farmed and aquatic animals, and we asked participants to indicate how intelligent (e.g., capable of remembering or planning) and sentient (e.g., experience pain or pleasure) each animal is. Participants also indicated how much they felt morally concerned for each animal. Importantly, some animals were listed twice but specified with a different food function such as a cow used for meat (beef cow) and a cow used for dairy (dairy cow), and a chicken used for meat (broiler chicken) and chicken used for eggs (layer chicken). We were particularly interested in whether pescatarians and vegetarians would be strategic in the attribution of moral worth and mental capacities to different types of animals in ways that suit their own consumption patterns.

And indeed, pescatarians and vegetarians showed a remarkable flexibility in extending moral concern and perceptions of animals’ capacities. They attributed moral status and mental capacities to a lower extent to dairy cows compared to beef cows, and to a lower extent to layer chickens compared to broiler chicken. In other words, people perceive the intelligence, sentience, and moral worth of animals in a selective and self-serving way, motivated by their dietary behaviour, even when evaluating the same animal but with a different function.

Along similar lines, of all dietary groups, pescatarians showed the largest discrepancy in moral concern and mind attribution between farmed land animals and aquatic animals, attributing particularly low levels of mental capacities and moral worth to aquatic animals.

How can you explain this type of apparent inconsistency in the perception of animals?

Our reasoning is that pescatarians and vegetarians may feel morally uncomfortable (cognitive dissonance) with the idea of contributing to the suffering of animals by consuming animal products (dairy, eggs, or fish products). Many of them have quit meat consumption out of concerns about animal rights and suffering, yet they continue drinking milk and eating eggs or fish and thus engage in consumption behaviours that involve enormous amounts of animal suffering. The findings suggest that pescatarians and vegetarians may resolve this cognitive dissonance by selectively downplaying the mental capacities and moral worth of the animals associated with their consumption behaviour. This way, they can avoid feeling morally troubled about the consumption of fish, dairy, or eggs, yet simultaneously express care and moral concern for animals by rejecting meat consumption.

Could it also be that people are just less aware of the ethical problems with the dairy or egg industry? If so, raising awareness about these issues could help with changing attitudes and behaviours. Isn’t that what you tested in your “Don’t Mind Milk?” article?

Correct! We conducted an experiment to test the impact of increased awareness of animal suffering in the dairy industry. My impression was that people may consider dairy consumption more ethical than meat consumption because they don’t link it with the killing of animals. They may also be unaware of harmful industry practices like the forced impregnation of cows, the separation of calves from their mothers, and the confined living conditions, causing severe health problems for the cows (e.g., bacterial infections, inflamed udders, and injuries to joints and knees). We wanted to investigate whether informing participants about these harmful conditions would change their perceptions of dairy cows and dairy consumption. Therefore, half of the participants read about a dairy cow living in these harmful conditions (high harm condition), whereas the other half read about a dairy cow that can spend time in outdoor areas and have decreased risk of health problems (low harm condition).

How did participants react to this information?

Participants informed about the harmful practices in the dairy industry felt more guilty about their dairy consumption compared to participants in the low harm condition. However, they also perceived the cow as less sentient and less intelligent. So again, minimizing or denying the mental capacities of animals seem to help people to feel better about their dairy consumption despite knowing the harm being done to animals.

At the same time, participants informed about the harmful dairy industry practices also expressed a greater willingness to reduce and stop dairy consumption. We don’t know if those intentions would also lead to actual reductions in dairy consumption, but these findings are more promising for animal advocacy efforts. Raising awareness about animal suffering in these industries tend to make people uncomfortable about their consumption behaviours and can make them reconsider their dietary habits.

This is also means consumers can show different reactions after becoming aware of the suffering of animals in the dairy industry and experienced feelings of guilt. Some people may react defensively and justify their animal product consumption, whereas others react empathetically and are open to change their dietary habits to align their consumption behaviour with their moral values and concern for animals.

Your findings on dairy reduction intentions are also generally consistent with previous findings, indicating that appealing to animal welfare appears to be effective in motivating people to reduce meat consumption.

Can you reflect on the implications of your findings for animal advocacy?

Across all studies, we see that consumers of animal products tend to use rationalizations and deny the sentience and intelligence of farmed animals to justify their animal product consumption. I think it is important to be aware that such psychological barriers may not only prevent meat consumers to reduce meat consumption but that similar barriers may also prevent vegetarians to reduce dairy and egg consumption. Animal advocacy campaigns could potentially address these barriers by increasing awareness of the mental capacities of farmed animals, directly confronting denial strategies, and promoting empathy. The use of visual imagery, compelling storytelling, and documentaries could be especially effective as these techniques can reduce the psychological distance between consumers and the animals.

When targeting animal product consumption among pescatarians and vegetarians, it is also worth keeping in mind that pescatarians and vegetarians typically hold more positive attitudes towards animals, compared to omnivores. Acknowledging their existing pro-animal attitudes, while emphasising that animal suffering is prevalent across all animal industries, can make pescatarians and vegetarians aware of the inconsistencies in their behaviour and increase their willingness to expand their plant-based food choices.

If you would like to get in touch with Maria: mioannidou5@gmail.com

Interview by Kristof Dhont

Photo credits: Jo-Anne McArthur / We Animals Media

Maria completed her PhD under supervision of Kathryn Francis, Barbara Stewart-Knox, and Valerie Lesk.

Key articles

Ioannidou, M., Francis, K. B., Stewart-Knox, B., & Lesk, V. (2024). Minding some animals but not others: Strategic attributions of mental capacities and moral worth to animals used for food in pescatarians, vegetarians, and omnivores. Appetite, 200, 107559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2024.107559

Ioannidou, M., Lesk, V., Stewart-Knox, B., & Francis, K. B. (2024). Don’t mind milk? The role of animal suffering, speciesism, and guilt in the denial of mind and moral status of dairy cows. Food Quality and Preference, 114, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2023.105082

Ioannidou, M., Lesk, V., Stewart-Knox, B., & Francis, K. B. (2023). Feeling morally troubled about meat, dairy, egg, and fish consumption: Dissonance reduction strategies among different dietary groups. Appetite, 190, 107024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2023.107024

Ioannidou, M., Lesk, V., Stewart-Knox, B., & Francis, K. B. (2023). Moral emotions and justifying beliefs about meat, fish, dairy and egg consumption: A comparative study of dietary groups. Appetite, 186, 106544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2023.106544

Authors: Nicholas Tan, Brock Bastian, and Luke Smillie (2024)

What’s the article about? (At a glance)

The ‘meat paradox’ encapsulates the conflict many people feel with regards to eating animals. Realising that one’s dietary practices contribute to harm to animals can be unpleasant. One way of reducing these negative feelings is by denying that farmed animals have sophisticated minds or suffer much. Of course, there are likely vast individual differences with regards to who experiences the meat paradox.

This Open Access PHAIR paper by Tan et al. (2024) explores how personality traits and ideological attitudes impact on how meat eaters experience and resolve the meat paradox via mind denial. Across two studies, self-identified omnivores were reminded of the harm involved in rearing farmed animals (cows or pigs) when considering meat-based meals, or they were not reminded of harm – similar to methods used by Bastian et al. (2012). Measures of mind attribution and negative affect were collected after the harm description. Participants also completed a range of personality and ideological measures such as Big Five personality traits (e.g., Openness to experience, Emotional volatility), preferences for inequality and group-based hierarchy (known as ‘Social Dominance Orientation‘) and conservatism. This way, the research team was able to explore whether participants’ responses to the harm information would be stronger or weaker depending on their personality traits and ideological attitudes.

Study 1 (N = 311) replicated the findings of Bastian et al. that harm descriptions led to lower mind attributions than the absence of harm – though negative feelings were unrelated to mind denial. Participants with higher (vs. lower) levels of Social Dominance Orientation and conservatism exhibited, overall, more animal-mind denial. Additionally, participants lower on Openness and higher on Emotion volatility engaged in more mind denial after learning about animal harm than those higher on Openness and lower on Emotion volatility.

Study 2 (N = 232) separated the harm information into “moderate” and “high” levels of harm, and sought to replicate and extend the findings of Study 1. Replicating Study 1, more mind denial occurred when participants read about the harm to farmed animals, and, this time, negative feelings correlated significantly with mind denial – that is, those who experienced more conflicted feelings exhibited more efforts to deny minds to farmed animals. The moderating effects of personality were less clear in Study 2, though Openness and Emotion Regulation Ability correlated with less mind denial.

Implications for advocacy

Knowing one’s audience and how they may respond to advocacy messages is important for optimising the effectiveness of advocacy efforts. The present findings highlight the need for targeted animal advocacy interventions that take into account the personality profile of audiences. Certain segments of the population are unlikely to respond sympathetically to messages about the suffering of farmed animals.

Based on Tan et al.’s findings, individuals higher in Social Dominance Orientation, conservatism, and Emotion volatility, and lower on Openness, are more likely to respond to such ‘harm’ messages with defensive reactions – for example, denying farmed animals minds – as a way of minimising the negative feelings caused by the meat paradox. By contrast, individuals higher in Openness and those better at regulating their emotions, may be more likely to respond positively – or at least less defensively – to such messages.

Blog post by Jared Piazza

Cover photo by Lucia Macedo

An interview with Maxim Trenkenschuh and Prof Chris Hopwood about their new research, published in Anthrozoos, that explores how personality differences relate to people’s support for farmed animal welfare legislation, like Proposition 12 in the United States.

Maxim, could you briefly introduce yourself?

Hi, my name is Maxim Trenkenschuh and I’m currently a PhD student at the University of Zurich. I’m interested in human-animal intergroup relations and I specifically want to find out how individual differences in people’s motives and personality predicts how they treat non-humans (e.g., whether they eat animals or not). I study this topic with my PhD supervisor, Professor Chris Hopwood. I currently live in Bonn, Germany with my partner and our son and work remotely. I also enjoy making music, drawing and skating.

You recently investigated the role of personality in people’s support for animal welfare legislation. What inspired this research and what were some of the key findings?

We conducted this research together with Courtney Dillard from Mercy For Animals. We were interested in general attitudes of the US population towards specific arguments for and against California Proposition 12. In contrast to a lot of previous work on how personality relates to attitudes about animals, we assessed personality using a more fine-grained measure that captures both broad (“big five”) domains as well as narrower facets of those domains. We did this because domain effects can miss important nuance. For instance, the Openness domain has features related to curiosity and creativity and other features related to intelligence, and these facets might be related to attitudes about animals in different ways.

For those of us unfamiliar with Proposition 12, could you briefly explain what it is, and how it relates to this study?

Proposition 12, also called Farm Animal Confinement Initiative, was a ballot initiative in California, which aimed at improving animal agriculture conditions by requiring more space for egg-laying hens, breeding pigs, and veal calves. It prohibits the sale of meat and eggs from animals confined in a noncomplying manner, regardless of whether the animals were raised in California or elsewhere. Since it also pressures out-of-state animal agriculture to conform with the requirements, it is considered one of the most important pieces of legislation by animal welfare advocates. The proposition was approved by California voters in 2018 but challenged by the National Pork Producers Council and the American Farm Bureau Federation at the Supreme Court of the US. The Supreme Court upheld Proposition 12 in 2023. This means it is now much easier for a particular state like California to influence animal welfare regulations not only within their own market but also among their out-of-state ‘providers’.

We are used to thinking of personality having to do with stable, but fairly general traits, that are not always predictive of situationally-based behaviour. What made you think that personality would matter for specific animal-advocacy actions, like supporting Proposition 12?

We now know that personality is less stable than was once thought, and in fact changes are normative during the transition to adulthood, at a time when many people are forming political opinions. Also, whereas no psychological variable is very predictive of behaviour in individual situations, there is a large body of evidence showing that personality traits are robust predictors of broad patterns of behaviour involving health, environmental behaviour, attitudes about social justice and compassion for animals. For instance, a recent meta-analysis showed that Openness and Agreeableness were reliable predictors of vegetarian and vegan dietary identity. These traits are also associated with more liberal and progressive political attitudes, which suggests they might predict the kinds of people who would support Proposition 12.

Which personality aspects did you expect to relate to support for Proposition 12 and why? Were there any unexpected or surprising findings, given your predictions?

Openness to experience appears to be an important aspect of personality for a range of concerns connected to nature and animals (e.g., pro-environmental attitudes). While associations between Openness and animal welfare attitudes are already well established, we wanted to explore Openness in a more granulated way. We expected that one specific component of Openness – the part related to curiosity and creativity – would principally drive the association. Indeed, this was the case. By contrast, aspects of Openness related to intellect actually had a weak, negative association with support for Proposition 12. The personality trait Agreeableness was also consistently associated with support for Proposition 12 and support for keeping it. But surprisingly it was the politeness aspect of Agreeableness, more than the compassionate aspect, that was predictive. Finally, the withdrawal aspect of Neuroticism was related to greater support for Proposition 12. We did not predict this finding, but interpreted it as possibly related to vystopia, i.e., the distress many vegans and people who support animal rights feel about the plight of farmed animals.

You found no evidence that age, gender, region, or political orientation moderated any of the trait-attitude relationships in the study. Why might this be, and what does this imply about the role of personality in animal advocacy?

Moderation effects are uncommon in studies like these, so this was not particularly surprising. It is well-known that moderation effects, when present, tend to be very small and thus very large samples are needed to find them. Although we had 802 people in our sample, it is possible that an even larger sample would have detected very mild moderation effects. More likely to us is that personality traits predict attitudes about animals similarly across demographic groups.

Next steps: How might personality matter for other forms of animal advocacy, such as joining organizations, participating in protests, advocating for vegan diets, etc.? Do you have plans to look at such trait-behavior relations?

Our team recently published a meta-analysis showing that the personality traits Extraversion, Openness, and Agreeableness are related to different kinds of civic engagement, such as advocacy, donating to organizations, joining organizations etc. (Stalhmann et al., 2023). When you consider these results in combination with previous studies about the traits that predict veg*n diet, compassion for animals, and support for animal welfare legislation, it seems that people who are more open and agreeable are both more likely to have more sympathetic attitudes towards animals and also to act on those attitudes. We are unaware of studies about which traits predict the people who are likely to become animal advocates specifically. This would be a natural extension of this work. Our work is currently focused on how changes in personality traits and dietary motives are related to changes in meat consumption and attitudes about animals. As I mentioned above, we know that personality traits can change at both the population and individual levels, and we are curious about how these changes predict changing attitudes in ways that could be leveraged for effective advocacy.

Interview questions and blog by Jared Piazza

Cover photo by Bill Fairs

An interview with Sophie Cameron, Matti Wilks, and Bastian Jaeger about their open-access PHAIR article, ‘Reduce by how much?‘, which considers what might be the optimal request we can make to consumers to hasten meat reduction.

Sophie, Matti and Bastian, could you each briefly introduce yourselves?

I’m Sophie Cameron, I completed my PhD and post-doctoral fellowship in moral developmental psychology at the University of Queensland. My research focuses on when children develop an understanding of moral character, and how it affects both their own behaviour and their evaluation of others’ behaviour. I am passionate about animal welfare and fascinated by the complicated relationship that human societies have with animals and meat.

I’m Matti Wilks, I’m a lecturer (assistant professor) in the Department of Psychology at the University of Edinburgh. I completed my PhD at the University of Queensland and was a postdoc at Princeton and Yale Universities. My research draws from social and developmental approaches to understand our moral motivations and actions. I am most fascinated by our moral circles and the factors that shape who we do and do not grant moral status to. In other research, I also examine attitudes towards cultured meat, as well as understanding the intersection between AI and psychology.

I’m Bastian Jaeger, I’m an assistant professor in the Department of Social Psychology at Tilburg University in the Netherlands. My background is in social cognition and behavioural economics and most of my research in the past focused on questions around first impressions – how we form them, how accurate they are, and how they influence decision-making. Once I had a more secure position in academia, I decided to look for a research topic where I felt that I could have more impact. Now, most of my research focuses on the intersection between animal welfare, moral psychology, and behaviour change. I am interested in applied questions, such as how to reduce meat consumption, and more foundational questions, such as how people think about the moral standing of non-human animals.

You recently investigated the topic of what might be the optimal request when approaching people about reducing their meat consumption. What inspired this research and what were some of the key findings?

There’s a long-standing debate about what is the most effective strategy for sustained behaviour change. Should we aim for incremental improvements that are easier to achieve, such as advocating for small reductions in meat consumption (e.g., Meatless Mondays) or minor changes in animal welfare standards? Or should we focus on a more demanding message, advocating for veganism or the abolition of factory farms? There are good arguments on both sides. Small changes might lead to complacency and prevent more important changes in the future, but they might also be more practical and feasible for people, slowly transforming public opinion and actually facilitating future changes. Ultimately, these are hypotheses that we should test – and that’s what we wanted to tackle in our paper.

In your recent PHAIR paper, you point out that asking people to completely eliminate meat from their diets may not be optimal to reduce overall meat consumption in the world. Why might this be the case?

Our paper is based on a simple, but also important observation. If the goal is to reduce how much meat is consumed overall, then we need to consider how many people consume how much meat. Different appeals that aim to reduce meat consumption likely impact these two variables in a different way. An appeal to eliminate meat consumption altogether may be ignored by most people because it is so demanding. But the few people that do comply with it change their consumption by a lot. So we get a lot of reduction, but only a few people taking action. Contrast that with what we might observe with a much less demanding appeal to cut, for example, 10% of meat from your diet. Many more people will probably comply with it because it’s easier to do, but they will only change their consumption by a little. So, we get a small reduction by a lot of people.

It’s not clear which strategy will lead to the greatest reduction in meat consumption overall. This depends entirely on how many people will comply with each appeal. It is also possible that the appeal that is optimal for overall meat reduction lies somewhere in the middle. That’s what we set out to test in our studies.

It’s not clear which strategy will lead to the greatest reduction in meat consumption overall. This depends entirely on how many people will comply with each appeal.

What did your research suggest in the most optimal request?

In our studies, we asked participants whether they would comply with meat reduction appeals that varied in how demanding they were. We first gave some reasons for reducing meat consumption and informed participants about the increasing number of people who are cutting back. Then participants indicated whether they would be open to reducing their meat consumption by different amounts, ranging from 10% all the way to 100%, for the duration of a week. We also asked them how much meat they eat in a typical week. This allowed us to look at two things.

First, as we suspected, we found that the more demanding the appeal was, the fewer participants agreed to cut their meat consumption by that amount (see Figure, left side). For example, in our sample of US participants, almost 90% said they would be open to reducing meat consumption by 10%, whereas only 25% said they would be open to eliminating meat from their diet entirely for a week (note that, although we encouraged participants to follow up on their intended reduction, we did not test whether they actually did, which means that the actual willingness to reduce consumption is likely lower).

More importantly, we could calculate for each requested reduction how much meat consumption was reduced overall. Our results consistently suggested that mid-range requests – asking for a reduction of around 50% – would be most effective in reducing overall meat consumption, more effective than the most demanding appeal (100% reduction) and the least demanding appeal (10% reduction) (see Figure, right side).

Was there much cross-cultural variability around this optimum?

What the optimal request is will ultimately depend on how many people are open to cutting back their meat consumption by various amounts. To get some idea of how much the optimal request varies, we ran the same analysis with four different groups of participants. We recruited a total of 500 people from Australia, the UK, and the United States via the online recruitment platform Prolific. These countries are, of course, relatively similar in terms of culture. Nonetheless, we were still a little surprised by how similar the results looked. In all three countries, mid-range requests around 50% were more effective than both the more demanding and the less demanding requests.

In all three countries, mid-range requests around 50% were more effective than both the more demanding and the less demanding requests.

We also recruited a sample of 200 university students from the Netherlands (participants represented in the above Figure). Overall, they were more open to reducing their meat consumption than our older, more demographically diverse participants from the Anglosphere. But we again saw that mid-range requests (50%-70%) were more effective than the more demanding and the less demanding requests.

There is, of course, more work that needs to be done here to understand how the optimal request varies across populations and which characteristics of a population are most important for determining the optimal request. However, our results suggest that mid-range requests around a 50% reduction may be better than much less or much more demanding requests.

Do you have a sense of whether mid-range requests are a feasible goal for most consumers?

It is safe to say that not every participant in our study who said they would be open to reducing their consumption by about 50% (which is about 60% of our US sample, for example) would actually do it. We also only asked about people’s willingness to reduce for a week. It is difficult to say how many people would try it but then go back to their regular diet after a week of reduction. We know that achieving widespread, sustained behaviour change is difficult, especially for behaviours that have a lot of “pull factors”. If I already eat meat, then continuing to do so is easier and more convenient in many ways.

Personally, we would guess that in the countries we studied, only a minority of people would try out a short-term reduction by about 50% and even fewer would stick to it over a period of months. Ultimately, we need more research that actually measures participants’ meat consumption in response to different requests to figure this out.

How would you like to see animal advocates applying your research?

Because of the many difficulties that we mentioned, it is difficult to make very confident recommendations. We would highlight two general points. A lot of discourse seems to focus on the extreme ends of a continuum: abolitionist approaches pushing for veganism versus small asks that could find broad adoption. Our findings suggest that the request that is most successful in reducing overall consumption may well lie somewhere in the middle of that spectrum.

More importantly, we hope that our paper shows one way in which this important question could be tested empirically. We think it’s important to adopt an evidence-based approach when trying to figure out what works best for the animals in the long run. Unfortunately, we often lack the strong evidence that is needed to address this question with confidence. It’s a difficult task and high-quality evidence often requires studies that are very time- and resource-intensive, for example, measuring participants’ actual meat consumption over longer periods of time. Our hope is that we will see more collaboration between advocacy groups and scientists on these questions in the future, for example, via forums such as PHAIR.

Questions and blog by Jared Piazza

Cover photo by amirali mirhashemian

An interview with Dr Marielle Stel about her recent research published in Anthrozoos on the value of perspective taking for attitude change. Do role reversal interventions work? If so, what might they be doing?

Marielle, could you briefly introduce yourself?

My name is Marielle Stel and I am currently working as an associate professor at the University of Twente (The Netherlands). I graduated as a social psychologist with specific interests in empathy and behaviour change. The research I’ve conducted so far can be broadly described as empowering individuals and society to enhance their safety for both physical threats (disasters and crises, including pandemics and climate change) as well as social threats (other people’s antisocial, egocentric behavior, deception). In my recent lines of work, I have been studying how to facilitate behaviour change towards a more compassionate and sustainable world, for instance, by aiming to increase the moral standing of animals. Regarding my personal interests, I love spending time with my four rescue cats, taking relaxing walks in nature, and bouldering.

You recently investigated a ‘role reversal’ intervention to change people’s attitudes and behavioural intentions towards using animals. What inspired this research and what were some of the key findings?

We were interested to what extent some of the existing interventions used by animal activists (e.g., Peta) would indeed lead to a change in attitudes and behaviours towards animals. We choose to investigate the role reversal intervention (click here for the video) as it included aspects that could theoretically change speciesism (e.g., creating awareness of how animals are being treated, facilitating taking the animal’s viewpoint, and emotional reactions towards observing unjustified suffering).

In two studies, we showed that this intervention led participants to more strongly intend to reduce their harmful behaviour towards animals, compared to a control condition with no video intervention. These behaviours included reducing the use of products for which animals were used (e.g., meat, dairy, cosmetics, medicines) and using animals for entertainment. Further analysis showed that this reduction in behavioural intentions was due to participants feeling a sense of injustice. There were no effects of the intervention on speciesist attitudes or signing an animal rights petition. So this intervention shows promise as people intended to change some behaviours that cause animals harm.

Could you say more about the ‘role reversal’ element of the video intervention. This seemed to depict animals as perpetrators of exploitative acts on humans. How might portraying humans as victims at the hands of animals increase our sympathy for animals who suffer at our hands?

We hypothesised that due to the role reversal element, the video may facilitate taking the animals’ viewpoint. Showing the reversed roles of animals and humans leads people to have to switch mentally. Furthermore, by showing a parallel world, activists hope that people become more aware of what we are doing to our animals and how awful this would be when the same would happen to us humans.

You are right that the animals become the perpetrators here, but it seems that the overarching message came across rather than the thought that animals would and could do that to humans. This is, for instance, reflected in increased feelings of injustice reported by participants when having watched the video, which in turn reduced intended harmful behaviours toward animals.

Do you worry that, in some contexts, it might backfire to portray animals as the perpetrators of violence?

I do not worry about that for the reasons just mentioned. However, if animals were portrayed as perpetrators of violence consistently and for a long period of time, for instance, in the media, on product packages, etc., it indeed may influence people’s attitudes towards animals negatively.

The ‘role reversal’ video seems to be increasing behavioural intentions via a sense of injustice. How might ‘role reversal’ images create this sense of injustice?

That is a good question. Feelings of injustice can be elicited when people learn about the suffering while taking perspective. So together with showing how animals are being treated (which does not necessarily have to be role reversed) and the role reversal aspect, this sense of injustice may have been elicited when watching the video. We did not find, however, that the video influenced perspective taking in itself, but it did influence feelings of injustice. Also, we did not have a condition showing these same pictures but without the role reversal. Thus, we cannot be certain whether this specific aspect of the video is necessary to obtain the effects.

Do you think this ‘role reversal’ method may be more effective than just having participants assume the perspective of victimised animals? Is this something you are currently testing?

No, I do not think it is necessarily more effective. Here, we were interested in whether these often-shared illustrations would actually have an effect. I believe that facilitating perspective taking more directly, for instance, by explicitly asking people to do so, might be more straightforward. Also, you do not have to worry about possible unwanted perpetrator effects.

We are not (yet) currently testing whether the video without role reversal would be as effective. We did conduct related studies on perspective taking. In two studies, we demonstrated that showing the suffering of animals alone is not sufficient to reduce speciesism (see preprint here). We showed that taking the perspective of the animals is crucial to obtain a reduction in speciesist attitudes and actual animal product consumption.

Importantly, the prejudice literature suggests that we should facilitate “imagine-self” perspective taking (imagining oneself in the situation of another individual) rather than “imagine-other” perspective taking (imagining how the other individual feels). Vorauer and Sasaki (2014) reported that the imagine-other perspective taking actually hindered prejudice reduction as this type of perspective-taking ironically led participants to focus more on how their own group was viewed by the outgroup rather than how the outgroup feels.

The video intervention was accompanied by sad music. Is the sad music essential to the intervention? Does it create a mood or tone that is essential for the intervention to work?

We did not test this, but I am guessing that the sad music is not essential for the intervention to work. It does create a mood that may strengthen the effect. That would be interesting to investigate. Happy music would probably reduce or neutralise the effects as some people may then interpret the illustrations as being funny.

The intervention altered people’s behavioural intentions but not their speciesist attitudes. Could your measure of speciesism be contributing to this null finding? (The Speciesism Scale is generally used to measure stable attitudes that vary between people rather than within.)

We agree it is indeed tricky to try and change such a stable attitude. Yet, we are interested in trying to find this ‘holy grail’: if/when people would change their beliefs about humans being morally superior, together with how morally acceptable they regard using animals for human aims. This would hopefully change their compassionate and sustainable behaviour more consistently. In the recently conducted perspective-taking studies I just talked about (see preprint), our intervention did reduce speciesist attitudes, measured with the Speciesism Scale.

Next steps: What are some outstanding questions from this research? Where would you like to take this research?

In general, my research focuses on the broader outstanding question of what aspects are needed to reduce speciesism and social dominance. Most people do not want to harm animals, yet they still do. I am interested in how to best inform and help people to reduce this inconsistency and overcome the many barriers that exist.

How would you like to see such an intervention applied by animal advocates?

The ‘how’ does not really matter to me, when the knowledge we create is helpful for animal advocates. When published, all interventions will be freely available to use. But the knowledge can be applied in other ways as well; for instance, by explicitly asking people to take the perspective of animals when showing images of animal suffering.

Questions for Dr Marielle Stel? She can be reached by email at m.stel@utwente.nl or via LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/marielle-stel-a110915/

Interview questions and blog by Jared Piazza

Cover photo by: Alexander Andrews

A study on meat and animal-product consumption in the Tesco 1.0 dataset

Cover photo by Bruno Kelzer

In this blog post, Rakefet, Chris, and Katharina provide an overview of their recent, open-access article, “Every little helps: Exploring meat and animal product consumption in the Tesco 1.0 dataset“, available here. They delve into the findings of their study, highlighting the benefits of using actual sales data and its implications for future research on meat reduction.

The Need for Behavioural Data on Meat Consumption

Meat and animal product consumption has been linked to several ethical, health, and environmental issues that affect our planet. The industry contributes to various environmental problems, such as climate change, deforestation, and the overuse of freshwater (Clark et al., 2020, Eshel et al., 2014, Theurl et al., 2020). Animal agriculture is a key contributor to global human-induced GHG emissions, emitting approximately 8.1 gigatons (Gt) carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2eq) (FAO, 2010), corresponding to 14.5% of global anthropogenic GHG emissions in 2013 (Gerber et al., 2013). According to the World Bank report, animal agriculture is also responsible for a large share of deforestation, for example, in the Amazon. Compared with 1970, 91% “of the increment of the cleared area has been converted to cattle ranching” (Margulis 2004, p. 9).

Animal agriculture also poses a threat to public health, exacerbating antibiotic resistance while constituting one of the most common sources of food-borne illness and zoonotic disease (Aiyar & Pingali, 2020; Canica et al., 2019; Fosse et al., 2008). Furthermore, animals bear the brunt of the impact, with, for example, 99% of U.S.-based farmed animals being raised on factory farms (Reese-Anthis, 2021). As factory farms are focused on efficiency and profit, they often disregard the natural needs and behavioural tendencies of animals (Broom, 1991), since the costs of raising animals humanely are often deemed economically unviable (Webster, 2001).

Although a great deal of recent research has focused on reducing meat consumption and promoting meat alternatives, most studies have relied on self-reported dietary data (e.g., see the review by Kwasny et al., 2022). This is where the importance of actual sales data for meat consumption research comes into play. Compared to self-reported data, actual sales data have an edge as they are more reliable and provide a better representation of dietary habits.

Compared to self-report data, actual sales data have an edge as they are more reliable and provide a better representation of dietary habits.

As self-reported data can often have biases and inaccuracies, analysts can use actual sales data to get a more accurate picture of what people are consuming. We used the Open Access Tesco 1.0 dataset (Aiello et al., 2020) to explore the consumption of meat and animal products in the UK, and identified regional, seasonal, and sociodemographic variations.

The Tesco 1.0 Dataset

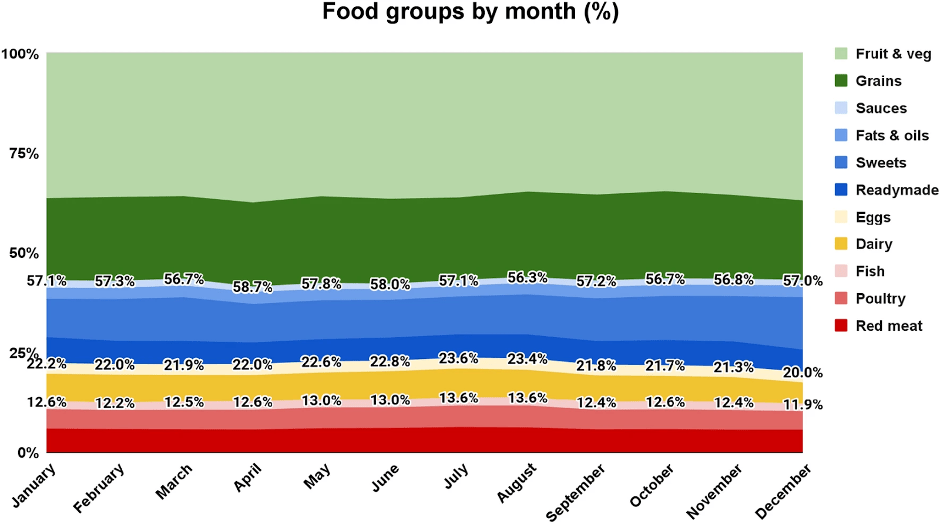

The Tesco 1.0 dataset plays a crucial role in providing valuable insights into actual dietary habits based on real food purchase data. It contains records of over 420 million real food purchases made by 1.6 million loyalty card holders across 411 Tesco stores in London in 2015. The data is aggregated most granularly at the level of monthly purchases of 11 broad food categories in 4833 lower super output areas (LSOA) – see figure 1 below.

Regional and Seasonal Variations

Our analysis of the Tesco 1.0 dataset shows that the spring and summer months had the highest consumption of meat and animal products, including poultry, which decreased in autumn (see figure 2 below). Though these seasonal trends in meat consumption are useful in identifying areas for meat-reduction campaigns, it is worth noting that the dataset only contains 12 months of data. Thus, seasonal trends cannot be identified over several years.

Sociodemographic Factors

To explore the socio-demographics of shoppers represented in the Tesco 1.0 dataset, we used another open access dataset – the LSOA Atlas – which provides summary demographics for each of the LSOAs in Greater London. This allowed us to identify several demographic predictors of meat consumption, some of which are surprising. For instance, it was found that areas with older, lower education, and more conservative voter-support had a lower proportion of meat purchases. This latter finding is interesting as it’s contrary to what self-report data at the individual-level might suggest about meat consumption as a function of political orientation (e.g., Hodson & Earle, 2018). On the other hand, the data also showed that a lower proportion of meat purchases could be observed in areas with a higher population density, better health, and more Hindus. These findings were in line with our hypotheses about meat consumption.

Benefits and Limitations

The dataset has some limitations, which are important to point out. Most notably, it only contains data for one grocery store, in one city, over one year and may not be generalisable to other times, locations, or retailers. The dataset also does not provide information on waste or how food was prepared. It also does not speak to the intentions behind the food purchases. For example, though the dataset provides information about the gender of the purchaser, it cannot illuminate whether the purchaser was shopping for themselves versus shopping for their partner or families. This is important to bear in mind when considering any gender differences in the data. Furthermore, some of the relationships we observed between demographic variables and meat purchases were relatively small, though statistically significant due to the large sample, and therefore should be interpreted with care.

Limitations aside, the Tesco 1.0 dataset can serve as a useful resource for meat reduction research. Our findings provide insights into regional, seasonal, and sociodemographic variations in animal product consumption. Future research using purchase data would benefit from datasets that relate to other parts of the UK, and internationally, to investigate wider cultural differences in meat consumption. Purchase data research would also benefit from having information on the family structure of shoppers, as well as having datasets that extend beyond a solitary year to consider seasonal trends in a more protracted manner.

About the Authors

Rakefet Cohen Ben-Arye is a social psychology Ph.D. student from Bar-Ilan University. Her research interests include animal advocacy, promoting plant-based choices, and alternative proteins. Rakefet can be reached by email: Rakefet.Cohen@live.biu.ac.il

Chris Bryant is the Director of Bryant Research, which works with animal charities and alternative protein companies to advance the protein transition. He has his PhD in Psychology from the University of Bath. Chris can be reached by email: Chris@Bryantresearch.co.uk

Katharina Hofman is a master’s graduate in behavioral science from the London School of Economics. Her particular research interests lie in the area of food consumption behavior and effective animal advocacy. Katharina can be reached by email: K.Hofmann@lse.ac.uk

This PHAIR blog was edited by: Jared Piazza