Researcher: Jessica Schiller

Affiliation: Department of Health Psychology, Johannes Kepler University Linz

Favourite animal: Cat

Contact information (email): jessica.schiller[at]jku.at

LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/jessica-schiller-6508b832b

What is the central topic or question of your PhD research? And what inspired you to pursue this topic/question?

I am doing my PhD in health psychology and I am broadly interested in the psychology of healthy and sustainable eating. A major part of that is meat and animal-product consumption. We know from research that, as a society, we need to reduce meat consumption for health, environmental, and animal-welfare reasons. At the same time, meat plays a central role in many people’s everyday diets. I live in Austria, where average meat consumption is quite high (around 58 kg per person per year), and where people are very culturally attached to meat products.

On a more personal level, I don’t eat animal products myself, which made me curious about how people think about meat, how they justify eating it, and why reducing meat consumption can be so difficult. When I was developing my PhD project, it quickly became clear that I wanted to understand how people can reduce their meat consumption, how they make sense of eating meat in the first place, and what psychological processes are involved. A big part of my work now looks at how people justify eating meat and how they react to different attempts or policies aimed at reducing meat consumption.

You recently published a paper titled, ” A license to eat meat? Exploring processes underlying the effect of animal labels on meat consumption”. Could you tell us a bit about the aim(s) of this study. Which theoretical perspectives did you draw upon and what were some of the key findings?

The main aim of this study was to better understand how animal labels on meat products influence people’s food choices. There is growing evidence that warning labels and graphic images can alter people’s choices – for example, reducing their intentions to purchase cigarettes, meat, or sugary drinks. But much less is known about the psychological processes behind these effects.

A key idea was to use animal images and systematically vary the valence of these to test their impact on purchasing decisions and explore some of the psychological processes that could be involved. The study draws upon theoretical perspectives including moral licensing, meat-animal dissociation, and emotional processes like empathy, guilt, and disgust. We wanted to test whether different types of animal labels might discourage meat consumption or, conversely, make people feel more justified in choosing meat.

In an experimental shopping task, we found that negative animal images reduced meat selection, mainly by disrupting dissociation processes and triggering emotional responses such as empathy and guilt. In other words, the images made it harder to mentally separate the meat product from the animal it came from. Neutral and positive images also reduced dissociation in the sense that people more clearly associated the product with the depicted animal. However, these images did not lower meat choice. In fact, positive images seemed to support justification processes, making it easier for people to feel comfortable choosing meat. Overall, the findings suggest that animal labels can operate through very different psychological mechanisms depending on how animals are portrayed and that only negative images appear to be effective in actually reducing meat consumption.

The labels that you used in your research included an animal welfare rating system (“Haltungsform”) alongside images of animals in neutral, positive or negative environments. Could you say more about this rating system and what it would mean to your Austrian participants. Is this a rating system that they would be familiar with?

The “Haltungsform” rating scale we used was inspired by the upcoming mandatory husbandry label for pig meat in Germany, which classifies farming conditions on a scale from basic indoor housing to organic (“Bio”). At first, we considered using only animal images, but we decided to combine them with a rating scale because we thought this would make the husbandry conditions more explicit and easier to grasp.

This kind of clear, welfare-based labeling does not yet exist in Austria. However, Austrian consumers are very familiar with the “AMA Gütesiegel”, which is widely known and trusted. The “Gütesiegel” is not primarily an animal-welfare label, it mainly signals an Austrian origin and certain quality standards. Consumers are also familiar with systems like the “Nutri-Score,” which provides a comparative evaluation of how healthy a product is within its category. So while Austrian consumers may not know the “Haltungsform” system specifically, the general idea of a rating scale on products is familiar. A more explicit welfare scale could therefore help make actual husbandry conditions more transparent.

Do you have a sense from your study if it was the image or the rating scale – or the combination of the two – that largely impacted on people’s food choices in the shopping task?

We cannot say for sure based on our study, because disentangling the effects of the images and the rating scale would require a different design. My sense is that it was likely the combination of both. The rating scale might have made the husbandry conditions explicit and cognitively accessible, while the images probably made them emotionally salient. The strongest effects were found in the negative condition, which led to the biggest reductions in meat selection. These images were taken from the Farm Transparency Project and show real animals in real farming environments. We deliberately avoided graphic or shocking content, but it was still clearly visible that the animals were not being treated well. The emotional impact is likely very powerful.

At the same time, previous research by Kranzbühler and Schifferstein has shown similar effects using animal images without a husbandry scale, but with “meat shaming” messages (e.g., “Eating meat makes animals suffer”). So my guess would be that the images carried much of the effect, whereas the rating scale may have reinforced the message and made it harder to ignore.

Could you tell us a little about the shopping task you had participants complete. Do you think your results would extend to consumer choices made within a physical store?

Participants completed an online shopping task in which they chose products from six common food categories. We deliberately selected everyday items people would typically encounter in a supermarket, for example, ready-made meals in the frozen foods section or different types of bread and baked goods. To keep things comparable, we used supermarket brands or no-name products across categories.

Of course, this setup differs in important ways from shopping in a physical store. In Austria, most people are not used to doing their grocery shopping online, and we only offered a limited selection of products per category. Some participants also noted that they would normally choose a different brand. So, it is important to keep in mind that these effects were observed within a partly constrained and artificial setting.

That said, there is good evidence that labels – visual information in particular – can influence real-world behaviour. Based on this, I do think that a combination of clear husbandry labels and images on meat packages could meaningfully influence consumer choices in physical stores as well. Yet, that is something future field studies really need to test directly.

Based on your findings, and thinking about food labels more generally, what would be your recommendations for animal-product labels? Are positive welfare labels likely to encourage purchases? Are there other elements of a label, beyond an image or rating scale, worth manipulating to discourage purchases?

Labels should be clear and easy to process. If they become too complex, people may simply ignore them. Generally speaking, visual elements are a good idea, and putting images of animals on products might be one way to make people think more about what they are consuming.

Another element of a label that could be manipulated might be the wording. Previous research by Kunst and colleagues has shown that the language used for meat products can create psychological distance between the animal and the product. This work shows that when the connection between the animal and the product is made more explicit – for example, by using the word “pig” instead of “pork” – people tend to rate the product as less appealing than when the connection is not made. So, a combination of wording, visual elements, and making husbandry conditions explicit might have even stronger effects.

Some of our readers may be opposed to animal welfare labels because they may simply change which animal products are purchased, as opposed to removing animal products from the market. Do you see animal welfare labels as part of a larger campaign that ultimately benefits animals and possibly even reduces the amount of animal products people consume?

I don’t see animal welfare labels as a solution on their own. I agree that, at least initially, they would mainly shift choices within the category of animal products rather than reduce consumption overall. However, this could still have meaningful effects. Products from poor animal husbandry are usually very cheap, and if these cheap products sell less, while higher-welfare products remain more expensive, this could indirectly lead people to buy less meat overall.

Ultimately, I see animal welfare labels as a first step to reduce meat consumption rather than an endpoint. A broader strategy would also need to address pricing, availability, and the attractiveness of plant-based alternatives. At the same time, we still need more research on how people react to more systemic measures, and whether such approaches might increase polarisation between meat-eaters and vegans. So, on their own, welfare labels are unlikely to transform the market. But combined with other measures, they have the potential to contribute to longer-term changes in eating habits.

“Welfare labels are unlikely to transform the market. But combined with other measures, they may have the potential to contribute to longer-term changes.”

Explore Jessica’s research further…

Key Papers by Jessica Schiller

Schiller, J., Ruby, M. B., & Sproesser, G. (2025). A license to eat meat? Exploring processes underlying the effect of animal labels on meat consumption. Appetite, 215, 108242. DOI Link

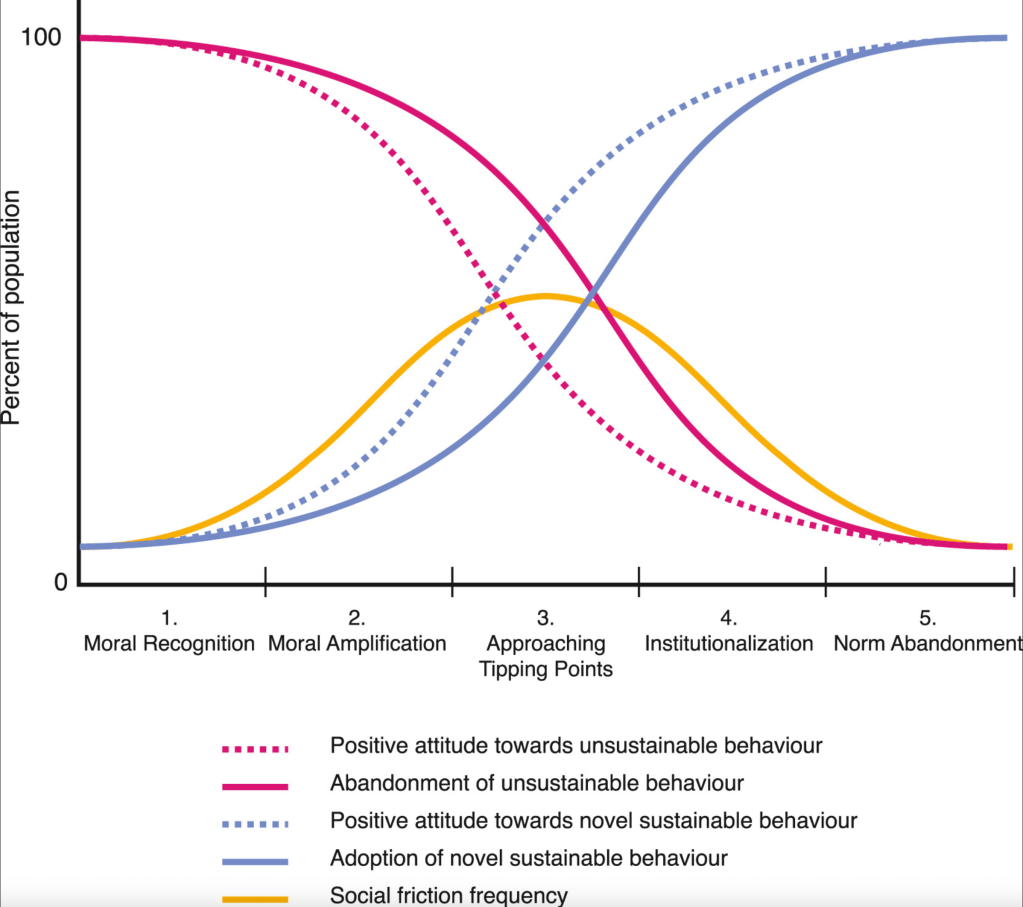

de Lint, L., Schiller, J., Gagliardi, L., & Sayat, R. A. (2026). Time matters: Temporal dimensions of change in animal-product consumption and animal attitudes. Psychology of Human-Animal Intergroup Relations, 5, e19183. DOI Link

Schiller, J., Northrope, K., Buttlar, B., Kashima, E., Ruby, M B., & Sproesser, G. (2026). Psychometric evaluation of the German version of the Motivations to Eat Meat Inventory (MEMI). Psychological Test Adaptation and Development, 7, 15-26. DOI Link

Blog by Jared Piazza; interview questions by Jared Piazza and Matthew Watkins.

Cover photo by: mathieu gauzy

An Interview with Fatma Sueda Evirgen

Sueda talks with us about her organisation, Animetrics, and shares recent findings on Turkish consumers’ perceptions of what farming practices are permitted under halal food production. The results highlight a “powerful entry point” for animal advocacy.

Sueda, could you briefly introduce yourself.

Hi, I’m Sueda (she/her). I’m a behavioural and experimental economist and a co-founder of Animetrics. I will soon be joining the Berlin Social Science Center (WZB) as a postdoctoral researcher on a project focusing on promoting prosocial behaviour. I recently completed my PhD in Economics at Tilburg University in the Netherlands, where my research focused on identifying biases—such as those based on ethnicity—and studying the causal effects of institutional structures on social and economic outcomes. Social justice has always been at the heart of both my academic work and personal commitments. In recent years, this commitment has expanded into advocacy for non-human animals. Together with my then-flatmate (now co-founder) Gülbike Mirzaoğlu, we started Animetrics to help bring evidence-based and accessible research to the animal advocacy movement. Alongside my academic work, I engage in cross-movement work, by organising talks that highlight the common ground between animal advocacy and other social justice movements to encourage collaboration and exchange of strategies.

You are one of the co-founders of Animetrics. Could you briefly introduce your organisation. What makes Animetrics unique?

Animetrics is a research and capacity-building organisation dedicated to supporting advocates with evidence-based insights and practical tools. We are a team of four: myself, my co-founder Gülbike Mirzaoğlu, and our long-term volunteers Megan Jamer and Sophie Weiner. Gülbike holds a PhD in Economics and specialises in social contagion and experimental economics. She also gives lectures on animal rights/welfare and environmental issues—having delivered over 25 so far, and counting—in collaboration with the Middle East Vegan Society. Megan is our fundraising advisor and has been helping us shape our fundraising efforts with a great mix of strategic insight and practical experience. Sophie is our creative design and communications volunteer, helping us make our research more accessible and engaging for a wider audience.

At Animetrics, we prioritise research projects based on the needs of advocates. This means working across a wide range of topics. At the moment, our primary focus is on understanding attitudes toward farmed animals within Muslim communities and the MENA region. We’re especially interested in the regional, cultural, and religious dynamics that shape how people engage with farmed animal issues.

Gülbike and I founded Animetrics after long conversations about how we could best contribute to the movement. In those discussions, we identified several critical gaps: while excellent research exists, very little is conducted in the Global South. Economists are largely underrepresented in this space, and, too often, research doesn’t reach advocates or address their most immediate needs. These gaps matter, because the advocacy movement operates with extremely limited resources, and we can’t afford to make strategic decisions without context-specific evidence. We use our expertise to fill these gaps.

What makes us unique is our integrated approach. We co-design research projects with advocates and support them in applying findings to real-world strategies. Our work includes original and collaborative studies, and free capacity-building services like research support and training for advocates and organisations on how to generate and use evidence effectively.

Your team recently published a report of research you did with Muslim consumers in Turkey, exploring their perceptions of what is “halal” when it comes to animal welfare practices. What inspired this research, and what were some of the key findings?

This research was inspired by personal experience. Through conversations in our Muslim families and communities, Gülbike and I often encountered the assumption that halal food automatically ensures high animal welfare standards. That is unfortunately not the case. Advocates working with Muslim populations echoed this perception and pointed out a lack of data on how widespread these beliefs are or how people might respond if they were corrected. That sparked our study.

We surveyed around 800 Muslim adults in Turkey, where halal is the norm for food production, to explore two questions:

- How much do consumers know about whether common industrial farming practices are allowed under halal rules?

- And how might learning the truth affect their willingness to buy these products or consider plant-based alternatives?

Participants were presented with six common practices linked to animal welfare concerns: chick culling, debeaking, cow and calf separation, lack of required long-term medical care, absence of protection for animals’ natural lifespans, and inadequate space for chickens to exhibit natural behaviours. They were asked whether they believed each practice was permitted under halal food production. If they answered incorrectly, we shared the correct information and then asked how it might influence their purchasing decisions and openness to plant-based options.

The results showed major knowledge gaps: for each practice, over half of our participants either believed it was forbidden or were unsure. Once informed, many said they’d be less likely to buy products involving those practices, and a smaller but meaningful share said they would consider plant-based alternatives. Responses varied across the sample. Certain groups—such as women, older adults, individuals who place high importance on halal, and those who view animal welfare as central to halal—were more likely to respond strongly to the new information.

The results showed major knowledge gaps: for each practice, over half of our participants either believed it was forbidden or were unsure.

What were some of the practices that consumers thought were forbidden under halal food production rules, but were in fact permitted?

The most widespread incorrect belief was the belief that long-term medical care is legally required in halal production systems. When presented with the statement, “In facilities where halal products are made, it is legally mandatory for animals with permanent injuries or who are no longer productive to receive long-term care and medical treatment,” nearly half (47.2%) of respondents incorrectly believed this is true. In reality, no such legal requirement exists within halal food production in Turkey.

A similar proportion (46.8%) also believed that halal standards require chickens to be given enough space to express natural behaviours—another incorrect assumption. Many participants also wrongly believed that the other farming practices were prohibited. In all cases, at least one in four participants held incorrect beliefs about what halal food production allows.

Your team observed that consumers with gaps in their understanding of what is halal showed increased intentions towards plant-based eating. What do you think explains their openness to shift their diet in response to learning that their assumptions were mistaken?

In our study, 70% of participants stated that they believe animal welfare is essential to halal. This suggests that welfare considerations may play a central role in how consumers evaluate the acceptability of animal products. When participants were presented with accurate information showing that certain industrial farming practices are permitted under halal standards, they may have experienced a sense of mismatch between what they believe halal should represent and what the industry currently allows. This may have triggered cognitive dissonance: a recognition that their beliefs about halal food conflicted with the actual conditions under which it is produced.

In this context, plant-based alternatives may have appeared more consistent with their ethical and religious values. This interpretation is supported by several patterns in the data. Participants who viewed animal welfare as central to halal were more likely to express increased intentions toward plant-based options, possibly because the new information directly challenged their beliefs. Similarly, those who had incorrectly believed a practice was prohibited under halal rules showed stronger shifts than those who were merely unsure, suggesting that this conflict shaped how participants responded. Another important insight is that beliefs about religious compatibility may shape openness to dietary change, as participants who saw plant-based diets as compatible with Islam were more likely to consider such alternatives.

How might Muslim consumers’ beliefs and commitments to eating halal be a platform for advocating for more plant-forward diets?

For many Muslim consumers, halal is not just a set of dietary rules. It’s closely tied to values such as compassion, stewardship, and avoiding unnecessary harm. This is reflected in the fact that a large share of participants in our study identified animal welfare as a core aspect of what halal means to them. This connection offers a powerful entry point for advocacy.

For many Muslim consumer, halal is not just a set of dietary rules. It’s closely tied to values such as compassion, stewardship, and avoiding unnecessary harm.

By highlighting where current production practices fall short of these values and showing how plant-based foods can meet halal requirements while avoiding animal welfare concerns, advocates can open constructive, values-aligned conversations. Framing plant-forward diets not only as compatible with Islamic principles but as an expression of them, may make these options more compelling. This is especially true when messages are tailored to resonate with cultural, religious, and ethical priorities within the communities being engaged.

See here to read the full report

For more information about Animetrics, visit their website here

Cover image by Tolis Dianellos

Interview and blog by Jared Piazza

For this week’s PHAIR blog, we are continuing our theme of dairy consumption – looking at psychological research that moves beyond the usual focus on meat consumption. I had a chat with Chelsea Davies and Samantha Stanley about their recent paper, “Untangling the dairy paradox: How vegetarians experience and navigate the cognitive dissonance aroused by their dairy consumption,” published in the journal Appetite. The paper explores whether vegetarians experience cognitive dissonance about consuming dairy products and, if so, what are the psychological consequences of these conflictual feelings – for example, do vegetarians rationalise their dairy consumption much like omnivores rationalise their meat consumption? Here’s what they had to say.

Chelsea and Samantha, could you each briefly introduce yourself?

My name is Chelsea Davies, and I am a Clinical Psychology Masters student at the University of Canberra in Australia. I first completed my honours degree in psychology at The Australian National University where I worked with Dr Samantha Stanley. Here, using a social psychological framework, we channelled our mutual interest in the negative impacts of the meat and dairy industry to guide our research. Specifically, we noticed there wasn’t much research on the psychology and rationalisation of dairy consumption, despite the theoretical and practical parallels to meat consumption (e.g., the impact on personal health, the animal, and the environment). I hope to continue exploring this field of social-environmental psychological research by integrating my clinical-based interests in the future.

I’m Dr Samantha Stanley and I’m a research fellow at the Institute for Climate Risk & Response at the University of New South Wales in Australia. In my work, I apply research and theory from social psychology to try to better understand the way that people think, feel, and act, in relation to climate change. My current role is funded by an Australian Research Council Early Career Fellowship and focuses on public attitudes towards policies that would support those most affected by climate change (e.g., resettlement for those at risk of displacement, compensation for Loss & Damage). I also have a strong personal interest in animal welfare and caring for the environment, which has shaped my research on the psychology of meat consumption and abstention.

Your new paper, “Untangling the dairy paradox”, extends work on the meat paradox to dairy consumption. Could you briefly summarise what the research was about and what you found.

In this paper, we aimed to test whether vegetarians experience cognitive dissonance about their dairy consumption. We had vegetarian participants complete an online survey about their motivations for being vegetarian and tell us about their recent dairy consumption. Then, we had half of them read about the ways that the dairy industry is harmful to animals, the environment, and human health. We found that those who read this message felt more guilty about their dairy consumption relative to those who did not read it, suggesting it induced cognitive dissonance. We wanted to know what vegetarians did with this cognitive dissonance – for example, would they ‘explain away’ or rationalise their dairy consumption as Natural, Necessary, Normal, and Nice (as found in meat-based research)? Interestingly, we found that, if anything, vegetarians were less likely to justify their dairy consumption, and more likely to contemplate reducing how much dairy they eat.

We found that, if anything, vegetarians were less likely to justify their dairy consumption, and more likely to contemplate reducing how much dairy they eat.

Work that has examined common arguments that meat eaters provide to defend meat consumption relate to four “N” categories: Necessary, Normal, Natural, and Nice. Your research suggests a fifth “N” applies to dairy justifications. What is that fifth “N” and how is it used to justify dairy consumption?

Chelsea had read widely on the 4Ns that justify meat consumption (and we are big fans of Jared’s work on this!). She found a Masters thesis by Sarah Kunze that uncovered a fifth “N”, Neglectable, in the context of dairy consumption. In this research, Sarah interviewed people in focus groups to hear about their justifications for consuming dairy. In doing so, she found some similar justifications that Jared and his colleagues found in relation to meat (e.g., that dairy is Normal to eat). But she also found a new category of justifications that seemed unique to dairy consumption. This fifth “N” (Neglectable) is used to justify dairy consumption by framing it as: (a) innocuous compared to meat (e.g., “Eating dairy products is better than eating other animal products”) and (b) so embedded in the food system that it’s unrealistic for people to completely cut it out (e.g., “Dairy products are too hard to avoid”). These examples are items in the scale we developed to measure the fifth “N”.

One surprising finding was that vegetarians who read about the environmental, animal welfare, and health issues linked to dairy defended dairy consumption on certain dimensions (e.g., its Naturalness) less than those who did not read about these issues. This is the opposite of what should occur if vegetarians were experiencing dissonance about their dairy consumption and were motivated to defend it. What does this result suggest about how vegetarians respond to potentially dissonance-arousing information about dairy?

In the cognitive dissonance literature, there are different avenues people can take to alleviate dissonance. Behaviour change isn’t a common route, especially for enjoyable behaviours like eating. A more common route is to justify one’s current behaviour, such as saying a food is too nice to give up (have you ever heard someone say they can’t go vegan because they love cheese too much?). Our results suggest that vegetarians in our sample did not try to alleviate cognitive dissonance by justifying their dairy consumption. Instead, they were more likely to acknowledge the problems with eating dairy by rating dairy consumption as less Natural and less Neglectable, and rating cows as having greater agency, when experiencing guilt about their consumption. Social identity theory offers one explanation for our unexpected finding. It is possible that when vegetarians in our sample read that dairy is equally as harmful to the environment, animals, and their bodies as meat, this threatened their sense of self. Then, to protect their identity as a value-conscious eater, they did not try to justify or defend their choice to eat dairy, and, instead, stated that they intended to reduce how much dairy they consume. Unfortunately, we didn’t have funds for a follow-up study to measure actual behaviour change, so we have no way to know if they followed through on this intention.

As a vegan, I find it easier to justify consuming dairy than meat. Indeed, it somehow “feels” less bad to consume an entire cheese pizza than a single pepperoni on a cheese pizza, even though I know that’s not true for the animals involved. Does your research into the dairy paradox help explain these irrational feelings I have about consuming dairy vs. meat?

This sounds like textbook “Neglectable” rationalising! We would hypothesise that it’s even easier to justify more ‘invisible’ ingredients too, like milk powder hidden in otherwise plant-based foods. We didn’t ask participants about their meat consumption or attitudes towards eating meat, but there are a few findings that are relevant here. Our cognitive dissonance induction reduced perceptions of dairy as Neglectable, which was associated with retaining higher levels of cognitive dissonance over time. In other words, seeing dairy as more Neglectable could help feelings of guilt pass. Perceiving dairy as a Neglectable food item could give people some protection from these guilty feelings when they hear about the negative aspects of the dairy industry. We also found a positive correlation between dairy consumption and Neglectable scores. This suggests that people who eat more dairy products also tend to see this behaviour as more Neglectable, so perhaps seeing dairy in this way helps vegetarians to keep eating cheese pizzas.

Cognitive dissonance is a powerful emotional state that can strengthen or change a behaviour.

What would you like vegan and animal advocates to take away from your research, and apply to their advocacy work?

One of the reasons we think our experiment led to behaviour change intentions rather than strengthening justifications for continuing to eat dairy is that we had participants commit to their vegetarian values (by telling us why they don’t eat meat) and report on their recent dairy consumption. This way, our experimental manipulation made the disconnect between their stated values and their behaviour very clear. Vegan and animal advocates could apply this in a few ways. The first is to consider tailoring their advocacy efforts to their audience. Vegetarians might respond differently to appeals to reduce their dairy consumption than meat eaters would to the same messaging. The second is to consider leveraging the reasons vegetarians give for abstaining from meat when explaining the problems with the dairy industry. For example, someone who has committed to abstaining from beef because they care deeply about cows might be more persuaded to change their dairy consumption if they are walked through the ways the dairy industry harms cows. Cognitive dissonance is a powerful emotional state that can strengthen or change a behaviour. Our research points to the importance of studying this process specifically within vegetarian samples and for dairy consumption, so that appeals can be tailored to the audience and the behaviour we’re hoping to change.

If you would like to get in touch with Chelsea and Samantha about their research: You can reach Chelsea by email at davies.a.chelsea@gmail.com and Samantha at s.stanley@unsw.edu.au

Interview and blog post by Jared Piazza

Cover photo by Hans Ripa

If you would like to read more about the ‘Dairy Paradox’ and the research discussed in this interview, please check out:

Davies, C. A., & Stanley, S. K. (2024). Untangling the dairy paradox: How vegetarians experience and navigate the cognitive dissonance aroused by their dairy consumption. Appetite, 203, 107692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2024.107692

We sit down with Dr. Sam Finnerty regarding his research into the “Scientist’s Dilemma in Climate Activism” – how scientists manage the potential identity tensions that arise from their involvement in climate activism and advocacy.

Sam, could you briefly introduce yourself?

My name is Samuel Finnerty. I am a Wellcome Trust funded Senior Research Associate at Lancaster University. My academic journey began in social and cultural anthropology with a degree and master’s at Maynooth University, followed by a master’s in cognitive science at University College Dublin. I then undertook a PhD in social psychology at Lancaster University under the supervision of Mark Levine and Jared Piazza. My research initially explored the intersection of scientists’ identities and environmental activism but has since extended to examining how higher education institutions themselves are responding to the climate and ecological crises. Beyond academia, I’m engaged in climate action, continually reflecting on the roles scientists and institutions play during this critical moment.

You recently investigated the topic of the scientist’s dilemma in climate activism. What is ‘the scientist’s dilemma’, and how does it relate to scientists’ involvement in activism?

The scientist’s dilemma arises from the tension between traditional scientific norms—objectivity, impartiality—and the moral urgency of the climate crisis. Scientists are essential to understanding and tackling the crisis, yet many struggle with balancing professional expectations and public action. On the one hand, scientists are expected to maintain their credibility as neutral observers; on the other, some feel a moral responsibility to ensure their findings lead to societal change. This dilemma often forces scientists to navigate competing imperatives: should they remain distant and neutral, or actively advocate for solutions based on their expertise?

In other work, you found that scientists who see their scientist and activist identities as compatible engage more in activism. Can you tell us a little about that work and what you found?

Our Nature Communications Earth and Environment paper demonstrated that the content of a scientist’s identity—how they perceive the relationship between science and activism—significantly predicted their engagement in activism. Scientists who viewed advocacy as compatible with scientific objectivity and saw environmental stewardship as a moral duty were more likely to participate in action. This same group of scientists was also less inclined to endorse techno-solutionism, a perspective that emphasises future technological solutions, while downplaying the need for systemic and political change. These findings underscore the importance of “inter-identity fit”, as scientists who align their values with activism are more willing to engage meaningfully in addressing the climate crisis.

Does your work suggest that certain individuals are more likely to struggle with the scientist’s dilemma than others?

Yes, certain groups of scientists are more likely to experience this dilemma. The traditional conception of scientists as impartial and apolitical—rooted in scientific norms of objectivity and detachment—can deter engagement for those who strongly adhere to these values. Such conceptions are often reinforced through professional norms, institutional cultures, and concerns about credibility or polarisation. However, many scientists challenge this traditional model, arguing that remaining “neutral” in the face of the climate crisis is morally and intellectually untenable. These tensions reflect diverse scientist identity constructions that can either hinder or enable action.

In your recent paper, you interviewed scientists from several countries and found that scientists confront and wrestle with the scientist’s dilemma using two different repertoires: By “reconceptualising scientist identity” and “reframing the work that scientists do”. Can you briefly explain what those repertoires involve?

In our paper, we found that scientists manage the “scientist’s dilemma” through two broad approaches. First, some challenge or reinterpret traditional views of what it means to be a scientist, aligning activism with their professional identity. For example, they may emphasise a moral duty to act, arguing that expertise creates an ethical responsibility to engage, or frame activism as a logical and objective response to scientific evidence – an extension of their role rather than a departure from it. Others reject the notion of “pure objectivity” altogether, suggesting that acknowledging personal values can lead to greater transparency and stronger scientific integrity.

For those less comfortable with activism, the focus shifts to their professional roles. They channel their efforts into research, teaching, and public communication, reframing these activities as deliberate forms of advocacy. Some carefully distinguish their engagement as “advocacy” rather than “activism”, reflecting concerns about credibility or professional norms while still contributing to change.

Ultimately, these different approaches illustrate the creative and strategic ways scientists resolve the dilemma, allowing them to engage with the climate crisis in ways that align with both their values and their professional identities.

Do you have a favourite quote from your interviews with scientists? Why is it your favourite?

One of my favourite quotes comes from an ecologist who captured the urgency and unique responsibility of scientists:

“I’m not just any scientist, I’m an earth scientist. I specifically know about what’s happening to the planet and […] my knowledge compels me to act […] because […] I worry that there might be people out there thinking “well, if it was really that bad then the scientists would be freaking out.” So, I think it’s important that we act like it’s an emergency […] it’s important that scientists are visibly freaking out.”

I find this quote particularly compelling because it highlights why many scientists feel driven to act publicly. If scientists appear calm and detached, the public may fail to grasp the scale and urgency of the crisis. For this ecologist, visible action is not just about raising awareness—it’s about embodying the seriousness of the situation and demonstrating that the climate crisis demands an immediate, collective response.

Your most recent work explored how scientists talk about the future in the context of the climate crisis. What did you find, and why does it matter?

We found that scientists talk about the future in very different ways. Some insist that societal collapse is inevitable, which often reflects a deep frustration about the scale of the crisis. Others see collapse as delay-able, but only if we act urgently. Then, there are those who focus on transformation, framing the future as something that can still be reshaped through human action.

What struck me was how these ways of talking about the future influence not just how scientists see their role, but also the kinds of solutions they argue for—whether it’s prepping for societal collapse, engaging in civil disobedience or collective action, or investing in technological innovation. Scientists aren’t just producing knowledge; they’re shaping how society imagines what is possible, which can make a real difference in how people think about and respond to the climate crisis.

You are a scientist yourself (a psychologist), and an activist. How has this informed the work that you are doing and your approach?

Being both a social psychologist and an activist provides me with a dual perspective. As a psychologist, I study how identities, norms, and values shape behaviour—key factors in understanding scientists’ engagement with activism. As an ethnographer actively involved in climate action, I’ve experienced firsthand the tensions I research, such as balancing professional credibility with moral responsibility. This combination allows me to approach the work with both critical insight and empathy, understanding how scientists navigate these challenges in their own lives.

What are some take-aways from your work that you would like all scientists on the fence about activism to know?

Activism doesn’t have to mean civil disobedience or public protest—there are many ways for scientists to advocate for change. This could involve reframing your research to address pressing environmental challenges, using your expertise to educate and engage the public, or influencing policy through outreach and communication. Importantly, activism and scientific objectivity are not mutually exclusive. Many scientists see advocacy as a natural extension of their role: using knowledge to inform action is part of what it means to be a scientist.

Finally, the urgency of the climate crisis prompts reflection. Choosing to remain silent or inactive is, in itself, a decision with consequences. For many scientists, advocacy and activism provides a way to reconcile their expertise with their sense of moral responsibility, ensuring their work contributes meaningfully to addressing the climate emergency.

If you would like to get in touch with Sam, he can be reached by email at s.finnerty [at] lancaster.ac.uk

You can also follow Sam on social media here: https://bsky.app/profile/samuelfinnerty.bsky.social

Interview questions and blog by Jared Piazza

Cover photo credit by: Andrea Domeniconi/Alamy Live News

An interview with Sophie Cameron, Matti Wilks, and Bastian Jaeger about their open-access PHAIR article, ‘Reduce by how much?‘, which considers what might be the optimal request we can make to consumers to hasten meat reduction.

Sophie, Matti and Bastian, could you each briefly introduce yourselves?

I’m Sophie Cameron, I completed my PhD and post-doctoral fellowship in moral developmental psychology at the University of Queensland. My research focuses on when children develop an understanding of moral character, and how it affects both their own behaviour and their evaluation of others’ behaviour. I am passionate about animal welfare and fascinated by the complicated relationship that human societies have with animals and meat.

I’m Matti Wilks, I’m a lecturer (assistant professor) in the Department of Psychology at the University of Edinburgh. I completed my PhD at the University of Queensland and was a postdoc at Princeton and Yale Universities. My research draws from social and developmental approaches to understand our moral motivations and actions. I am most fascinated by our moral circles and the factors that shape who we do and do not grant moral status to. In other research, I also examine attitudes towards cultured meat, as well as understanding the intersection between AI and psychology.

I’m Bastian Jaeger, I’m an assistant professor in the Department of Social Psychology at Tilburg University in the Netherlands. My background is in social cognition and behavioural economics and most of my research in the past focused on questions around first impressions – how we form them, how accurate they are, and how they influence decision-making. Once I had a more secure position in academia, I decided to look for a research topic where I felt that I could have more impact. Now, most of my research focuses on the intersection between animal welfare, moral psychology, and behaviour change. I am interested in applied questions, such as how to reduce meat consumption, and more foundational questions, such as how people think about the moral standing of non-human animals.

You recently investigated the topic of what might be the optimal request when approaching people about reducing their meat consumption. What inspired this research and what were some of the key findings?

There’s a long-standing debate about what is the most effective strategy for sustained behaviour change. Should we aim for incremental improvements that are easier to achieve, such as advocating for small reductions in meat consumption (e.g., Meatless Mondays) or minor changes in animal welfare standards? Or should we focus on a more demanding message, advocating for veganism or the abolition of factory farms? There are good arguments on both sides. Small changes might lead to complacency and prevent more important changes in the future, but they might also be more practical and feasible for people, slowly transforming public opinion and actually facilitating future changes. Ultimately, these are hypotheses that we should test – and that’s what we wanted to tackle in our paper.

In your recent PHAIR paper, you point out that asking people to completely eliminate meat from their diets may not be optimal to reduce overall meat consumption in the world. Why might this be the case?

Our paper is based on a simple, but also important observation. If the goal is to reduce how much meat is consumed overall, then we need to consider how many people consume how much meat. Different appeals that aim to reduce meat consumption likely impact these two variables in a different way. An appeal to eliminate meat consumption altogether may be ignored by most people because it is so demanding. But the few people that do comply with it change their consumption by a lot. So we get a lot of reduction, but only a few people taking action. Contrast that with what we might observe with a much less demanding appeal to cut, for example, 10% of meat from your diet. Many more people will probably comply with it because it’s easier to do, but they will only change their consumption by a little. So, we get a small reduction by a lot of people.

It’s not clear which strategy will lead to the greatest reduction in meat consumption overall. This depends entirely on how many people will comply with each appeal. It is also possible that the appeal that is optimal for overall meat reduction lies somewhere in the middle. That’s what we set out to test in our studies.

It’s not clear which strategy will lead to the greatest reduction in meat consumption overall. This depends entirely on how many people will comply with each appeal.

What did your research suggest in the most optimal request?

In our studies, we asked participants whether they would comply with meat reduction appeals that varied in how demanding they were. We first gave some reasons for reducing meat consumption and informed participants about the increasing number of people who are cutting back. Then participants indicated whether they would be open to reducing their meat consumption by different amounts, ranging from 10% all the way to 100%, for the duration of a week. We also asked them how much meat they eat in a typical week. This allowed us to look at two things.

First, as we suspected, we found that the more demanding the appeal was, the fewer participants agreed to cut their meat consumption by that amount (see Figure, left side). For example, in our sample of US participants, almost 90% said they would be open to reducing meat consumption by 10%, whereas only 25% said they would be open to eliminating meat from their diet entirely for a week (note that, although we encouraged participants to follow up on their intended reduction, we did not test whether they actually did, which means that the actual willingness to reduce consumption is likely lower).

More importantly, we could calculate for each requested reduction how much meat consumption was reduced overall. Our results consistently suggested that mid-range requests – asking for a reduction of around 50% – would be most effective in reducing overall meat consumption, more effective than the most demanding appeal (100% reduction) and the least demanding appeal (10% reduction) (see Figure, right side).

Was there much cross-cultural variability around this optimum?

What the optimal request is will ultimately depend on how many people are open to cutting back their meat consumption by various amounts. To get some idea of how much the optimal request varies, we ran the same analysis with four different groups of participants. We recruited a total of 500 people from Australia, the UK, and the United States via the online recruitment platform Prolific. These countries are, of course, relatively similar in terms of culture. Nonetheless, we were still a little surprised by how similar the results looked. In all three countries, mid-range requests around 50% were more effective than both the more demanding and the less demanding requests.

In all three countries, mid-range requests around 50% were more effective than both the more demanding and the less demanding requests.

We also recruited a sample of 200 university students from the Netherlands (participants represented in the above Figure). Overall, they were more open to reducing their meat consumption than our older, more demographically diverse participants from the Anglosphere. But we again saw that mid-range requests (50%-70%) were more effective than the more demanding and the less demanding requests.

There is, of course, more work that needs to be done here to understand how the optimal request varies across populations and which characteristics of a population are most important for determining the optimal request. However, our results suggest that mid-range requests around a 50% reduction may be better than much less or much more demanding requests.

Do you have a sense of whether mid-range requests are a feasible goal for most consumers?

It is safe to say that not every participant in our study who said they would be open to reducing their consumption by about 50% (which is about 60% of our US sample, for example) would actually do it. We also only asked about people’s willingness to reduce for a week. It is difficult to say how many people would try it but then go back to their regular diet after a week of reduction. We know that achieving widespread, sustained behaviour change is difficult, especially for behaviours that have a lot of “pull factors”. If I already eat meat, then continuing to do so is easier and more convenient in many ways.

Personally, we would guess that in the countries we studied, only a minority of people would try out a short-term reduction by about 50% and even fewer would stick to it over a period of months. Ultimately, we need more research that actually measures participants’ meat consumption in response to different requests to figure this out.

How would you like to see animal advocates applying your research?

Because of the many difficulties that we mentioned, it is difficult to make very confident recommendations. We would highlight two general points. A lot of discourse seems to focus on the extreme ends of a continuum: abolitionist approaches pushing for veganism versus small asks that could find broad adoption. Our findings suggest that the request that is most successful in reducing overall consumption may well lie somewhere in the middle of that spectrum.

More importantly, we hope that our paper shows one way in which this important question could be tested empirically. We think it’s important to adopt an evidence-based approach when trying to figure out what works best for the animals in the long run. Unfortunately, we often lack the strong evidence that is needed to address this question with confidence. It’s a difficult task and high-quality evidence often requires studies that are very time- and resource-intensive, for example, measuring participants’ actual meat consumption over longer periods of time. Our hope is that we will see more collaboration between advocacy groups and scientists on these questions in the future, for example, via forums such as PHAIR.

Questions and blog by Jared Piazza

Cover photo by amirali mirhashemian

A study on meat and animal-product consumption in the Tesco 1.0 dataset

Cover photo by Bruno Kelzer

In this blog post, Rakefet, Chris, and Katharina provide an overview of their recent, open-access article, “Every little helps: Exploring meat and animal product consumption in the Tesco 1.0 dataset“, available here. They delve into the findings of their study, highlighting the benefits of using actual sales data and its implications for future research on meat reduction.

The Need for Behavioural Data on Meat Consumption

Meat and animal product consumption has been linked to several ethical, health, and environmental issues that affect our planet. The industry contributes to various environmental problems, such as climate change, deforestation, and the overuse of freshwater (Clark et al., 2020, Eshel et al., 2014, Theurl et al., 2020). Animal agriculture is a key contributor to global human-induced GHG emissions, emitting approximately 8.1 gigatons (Gt) carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2eq) (FAO, 2010), corresponding to 14.5% of global anthropogenic GHG emissions in 2013 (Gerber et al., 2013). According to the World Bank report, animal agriculture is also responsible for a large share of deforestation, for example, in the Amazon. Compared with 1970, 91% “of the increment of the cleared area has been converted to cattle ranching” (Margulis 2004, p. 9).

Animal agriculture also poses a threat to public health, exacerbating antibiotic resistance while constituting one of the most common sources of food-borne illness and zoonotic disease (Aiyar & Pingali, 2020; Canica et al., 2019; Fosse et al., 2008). Furthermore, animals bear the brunt of the impact, with, for example, 99% of U.S.-based farmed animals being raised on factory farms (Reese-Anthis, 2021). As factory farms are focused on efficiency and profit, they often disregard the natural needs and behavioural tendencies of animals (Broom, 1991), since the costs of raising animals humanely are often deemed economically unviable (Webster, 2001).

Although a great deal of recent research has focused on reducing meat consumption and promoting meat alternatives, most studies have relied on self-reported dietary data (e.g., see the review by Kwasny et al., 2022). This is where the importance of actual sales data for meat consumption research comes into play. Compared to self-reported data, actual sales data have an edge as they are more reliable and provide a better representation of dietary habits.

Compared to self-report data, actual sales data have an edge as they are more reliable and provide a better representation of dietary habits.

As self-reported data can often have biases and inaccuracies, analysts can use actual sales data to get a more accurate picture of what people are consuming. We used the Open Access Tesco 1.0 dataset (Aiello et al., 2020) to explore the consumption of meat and animal products in the UK, and identified regional, seasonal, and sociodemographic variations.

The Tesco 1.0 Dataset

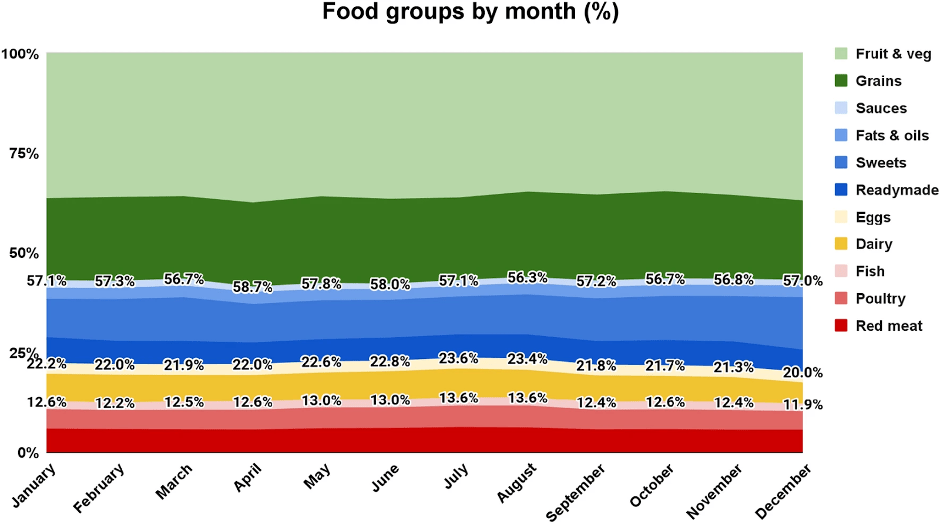

The Tesco 1.0 dataset plays a crucial role in providing valuable insights into actual dietary habits based on real food purchase data. It contains records of over 420 million real food purchases made by 1.6 million loyalty card holders across 411 Tesco stores in London in 2015. The data is aggregated most granularly at the level of monthly purchases of 11 broad food categories in 4833 lower super output areas (LSOA) – see figure 1 below.

Regional and Seasonal Variations

Our analysis of the Tesco 1.0 dataset shows that the spring and summer months had the highest consumption of meat and animal products, including poultry, which decreased in autumn (see figure 2 below). Though these seasonal trends in meat consumption are useful in identifying areas for meat-reduction campaigns, it is worth noting that the dataset only contains 12 months of data. Thus, seasonal trends cannot be identified over several years.

Sociodemographic Factors

To explore the socio-demographics of shoppers represented in the Tesco 1.0 dataset, we used another open access dataset – the LSOA Atlas – which provides summary demographics for each of the LSOAs in Greater London. This allowed us to identify several demographic predictors of meat consumption, some of which are surprising. For instance, it was found that areas with older, lower education, and more conservative voter-support had a lower proportion of meat purchases. This latter finding is interesting as it’s contrary to what self-report data at the individual-level might suggest about meat consumption as a function of political orientation (e.g., Hodson & Earle, 2018). On the other hand, the data also showed that a lower proportion of meat purchases could be observed in areas with a higher population density, better health, and more Hindus. These findings were in line with our hypotheses about meat consumption.

Benefits and Limitations

The dataset has some limitations, which are important to point out. Most notably, it only contains data for one grocery store, in one city, over one year and may not be generalisable to other times, locations, or retailers. The dataset also does not provide information on waste or how food was prepared. It also does not speak to the intentions behind the food purchases. For example, though the dataset provides information about the gender of the purchaser, it cannot illuminate whether the purchaser was shopping for themselves versus shopping for their partner or families. This is important to bear in mind when considering any gender differences in the data. Furthermore, some of the relationships we observed between demographic variables and meat purchases were relatively small, though statistically significant due to the large sample, and therefore should be interpreted with care.

Limitations aside, the Tesco 1.0 dataset can serve as a useful resource for meat reduction research. Our findings provide insights into regional, seasonal, and sociodemographic variations in animal product consumption. Future research using purchase data would benefit from datasets that relate to other parts of the UK, and internationally, to investigate wider cultural differences in meat consumption. Purchase data research would also benefit from having information on the family structure of shoppers, as well as having datasets that extend beyond a solitary year to consider seasonal trends in a more protracted manner.

About the Authors

Rakefet Cohen Ben-Arye is a social psychology Ph.D. student from Bar-Ilan University. Her research interests include animal advocacy, promoting plant-based choices, and alternative proteins. Rakefet can be reached by email: Rakefet.Cohen@live.biu.ac.il

Chris Bryant is the Director of Bryant Research, which works with animal charities and alternative protein companies to advance the protein transition. He has his PhD in Psychology from the University of Bath. Chris can be reached by email: Chris@Bryantresearch.co.uk

Katharina Hofman is a master’s graduate in behavioral science from the London School of Economics. Her particular research interests lie in the area of food consumption behavior and effective animal advocacy. Katharina can be reached by email: K.Hofmann@lse.ac.uk

This PHAIR blog was edited by: Jared Piazza