An Interview with Dr Maddie Judge on the dynamics of moralised social change

Maddie, could you briefly introduce yourself?

Kia ora! My name is Maddie Judge and I’m a lecturer in marketing at the University of Otago in Aotearoa, New Zealand. My academic background is in social and environmental psychology, and I focus on understanding how to promote the adoption of pro-environmental behaviours – ranging from individual behaviours to more political behaviours. More recently, I’ve focused on understanding the social psychological aspects of sustainability transitions, like the protein transition. In my free time, I enjoy spending time with my whānau (family) in nature.

Your recent paper, “Accelerating social tipping points in sustainable behaviors: Insights from a dynamic model of moralized social change” considers how moral innovators might inspire social tipping points. Could you walk us through how the dynamics in your model might play out in the real-world example of plant-forward eating?

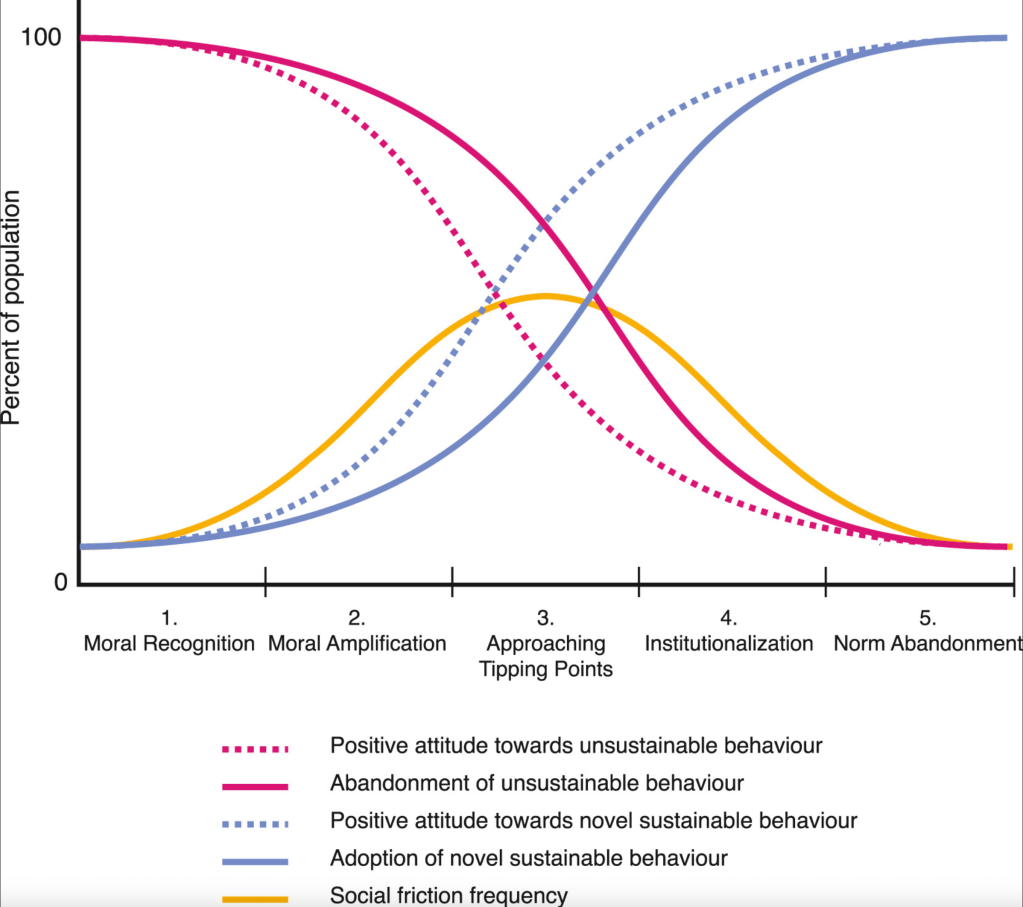

In our Dynamic Model of Moralized Social Change, we theorise how moralisation (i.e., starting to view a behaviour as having a moral quality) influences social tipping points in behaviour change. Social tipping points are social change thresholds that are followed by rapid and widespread changes in human behaviour, such that the adoption of a behaviour, like plant-based eating, becomes self-sustaining. Our model presents five key phases in this process:

- moral recognition

- moral amplification

- approaching social tipping points

- institutionalisation

- norm abandonment

In the case of plant-forward eating in societies that have high levels of animal product consumption, the moral recognition phase focuses on the actions of a minority of “moral innovators” – individuals who deviate from dominant social norms for moral reasons – like vegans rejecting products of animal exploitation and adopting plant-based diets. In this first phase (see the figure below), vegans are often stigmatised and ostracised as ‘oddballs’ due to their deviation from the meat-eating norm, and their moral arguments are not widely acknowledged as legitimate. This may lead to the formation of clusters of moral innovators who can bond over their shared behaviour and provide each other social support.

In the moral amplification phase, more people start to become aware of the moral nature of the novel behaviour, and perhaps start to experience uncertainty about the morality of their own behaviour, partly due to the sustained actions of moral innovators. In this phase, there may be increased levels of debate and social conflict. This may contribute to individuals strategically hiding their moral views, and a situation where internal shifts in attitudes (e.g., awareness of moral issues with animal agriculture and one’s involvement as a consumer) may not yet be aligned with a corresponding shift in behaviours (e.g., eating less meat). However, once a critical mass is reached, social tipping points may occur, in which more and more people start to adopt plant-based diets and products.

At later stages in the diffusion process (i.e., institutionalisation and norm abandonment), the novel behaviour can gain institutional support (e.g., government policies to promote plant-based products) and the dominant social norms may even switch so that ordering a meat-based meal is seen as the controversial choice, or as a behaviour that is specific to certain minority groups.

What distinguishes your Dynamic Model of Moralised Social Change from traditional models of behavioural change or diffusion of innovation, especially in the context of sustainability?

Our approach attempts to integrate various insights from different disciplines into a broad theoretical model. In psychology, most traditional models of behaviour change focus on change within individuals, usually within the timeframe of a single experiment or cross-sectional survey, rather than longer-term changes within individuals or changes involving entire groups or populations. Conversely, most sociological models of social change, such as diffusion of innovations theory (Rogers, 1962) and more recent work on network dynamics and complex contagion (Centola, 2018), focus on network characteristics or structural factors, rather than individuals and internal psychological processes. We aim to contribute a novel perspective to these approaches by theorising how internal processes of moralisation may impact on social interactions and the longer-term diffusion of sustainable behaviours across entire populations.

Furthermore, we began from a starting point of grassroots, bottom-up social change and considered how this might interact organically with top-down political, legal and market-related changes in the social environment. This is a bit different to most research on social norm interventions, which often start from a top-down perspective of how the government might implement such interventions.

You describe moralisation as a “double-edged sword” – that can both inhibit and speed up social change. What do you mean by this?

Moralisation (i.e., connecting a moral value to a behaviour) can be a powerful motivator that compels people to take action – by both changing their own behaviour, and by trying to convince others to change their behaviour. However, moralisation can also contribute to social conflict. For instance, when we are confronted by someone who claims to be acting more morally than we are, rather than feeling inspired to change, we can often feel threatened. This can lead us to derogate the source of the message (known as “do-gooder derogation“; Minson & Monin, 2012).

My co-authors and I argue that, at a collective level, these processes of moralisation and social conflict are likely to delay social tipping points, because they disrupt the communication channels required for the diffusion of ideas and behaviours. However, once a tipping point is reached, moralisation can speed up social change – in part because individuals who have moralised the issue will be motivated to enforce new social norms. This social change is also likely to be more enduring than change that is not driven by moral concerns.

In the context of plant-forward diets, how can advocates communicate issues of morality in a way that does not slow change?

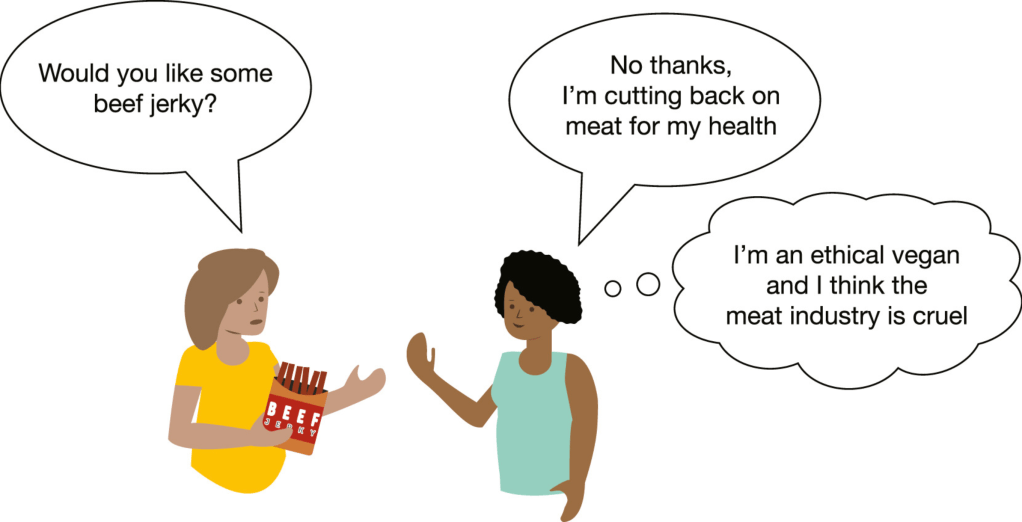

Individual adopters often experience a dilemma between wanting to communicate their moral motives with the hope of persuading others to follow suit, and wanting to avoid being viewed negatively or socially excluded for judging others.

More research is needed on how advocates can effectively navigate such conversations. Nonetheless, a few initial ideas spring to mind:

First, our model suggests that the stage of the diffusion process may affect whether individual adopters can safely reveal their moral motives. Specifically, it may become easier to discuss moral motives once there is widespread recognition of the moral nature of the behaviour. This means that, potentially, adopters could consider adapting their strategy to where they think others are in this process. For example, downplaying moral motives to avoid being ostracised might be a necessary strategy in the early stages of diffusion. However, revealing one’s moral motives may be important for breaking the “spiral of silence” in later phases. Interestingly, research suggests we are often poor judges of the speed of cultural change, so we might currently be underestimating how open others are to hearing moral motives – if presented in a gentle way.

We are often poor judges of the speed of cultural change, so we might currently be underestimating how open others are to hearing moral motives – if presented in a gentle way.

Second, it might also help to keep in mind that, as an individual, you are just one part of a collective effort, and that other actors (e.g., non-profits) can also help raise awareness of the moral implications of behaviours.

Lastly, it might help to consider some insights from the research on complex contagion; for example, if you can aim to attend social events with at least two or three other plant-based friends, that might help contribute to the multiple exposures needed for others to consider changing their behaviour.

In the paper, you outline a couple of recommendations for moral innovators to correct misperceptions about how much social support there is for change. This includes that innovators “maintain their perceived status as part of the group” and “share their opinions publicly”. What might this look in practice?

Although being part of a community of moral innovators can be helpful for providing one another social support, in order to be able to influence wider social norms, it is also important to stay connected to different communities. People are motivated to pay attention to changing social norms in their environment, but not if they believe that the norm is something limited to a particular group (e.g., the practices of a specific religious group). So, in the context of plant-based diets, vegans need to be seen as legitimate members of common social groups (e.g., fathers, footballers, teachers, etc.) in order to be able to contribute to shifting social norms in those contexts.

To be able to influence wider social norms, it is important to stay connected to different communities.

Related to this, some of my research has looked at the role of a vegan social identity in helping vegans to maintain their behaviours and attempt to influence others. Having a vegan social identity may be particularly important in the early stages of diffusion, to help identify like-minded individuals and to offer and receive social support. However, as mainstream interest in plant-forward eating grows, the social identity of vegans may need to become less central or a new form of the identity may need to be developed.

What would you say to those who hold the pessimistic view that individual behaviour change is unlikely to lead to widespread social change?

I agree that promoting individual behaviour change on its own is unlikely to lead to widespread social change, but I think it is an important element of the change process. As individuals, changing our everyday behaviours (e.g., by adopting a plant-based diet) may not only have a concrete impact but may also influence other people and shape perceived social norms, leading to ripple effects across society (see below).

My view is that when it comes to addressing the harmful impacts of human behaviours, bottom-up approaches like these that aim to shift everyday social norms and practices will be needed alongside more stringent top-down policies, in order to make the alternative behaviour seem more feasible, normal and attractive. If we attempt to enact top-down policies without also incorporating bottom-up approaches to shifting widespread social norms and practices, I believe there is likely to be greater resistance and polarisation in response to such policies.

Do you think we’re currently seeing signs that plant-forward diets are approaching a tipping point? What are the key signals to watch for?

The notion of social tipping points has recently become quite popular with policymakers and researchers because it sounds like a simple and effective way to promote rapid social change – which is what we need in order to address the climate crisis and other urgent issues such as the scale of animal suffering in industrial farming systems. However, in reality, it can take years or decades of activists’ efforts to get to a point where social tipping points may occur. I think there is reason to believe that some countries may be approaching social tipping points around plant-based diets, though.

Here in Aotearoa, I think we’re still a way off, but in other countries (e.g., Denmark, the Netherlands), there has been much more visible shifts in that direction. I would love to do some cross-national research to try to figure out where different countries are at in our diffusion model. This is also an interesting time because there are some claims of the plant-based or vegan “bubble” bursting (this is also known as the “trough of disillusionment” in the Gartner Hype Cycle). I am curious to see which elements of change will be able to make it through this period.

What do you hope activists, researchers, or policymakers take away from your model that might change how they approach plant-forward dietary transitions?

There are a few things I might suggest:

First, apparent backlash and social conflict is not necessarily a sign that a cause is doomed to fail. Instead, it can signal that the cause is related to something that most people care deeply about like animal welfare.

Second, moralisation can be an important part of the process of social change. However, it is also important to create the conditions in which people can start to see their behaviour as a choice. For example, by having attractive, low-cost plant-based alternatives widely available, this makes choosing the plant-based option easier, seem normal, and not in conflict with various social identities.

Finally, I’d recommend staying optimistic and sharing your experiences, because social diffusion happens when people share their views rather than self-silence, and social diffusion happens more often than you think!

If you would like to get in touch with Maddie, they can be reached via email: maddie.judge@otago.ac.nz

Coverphoto by Michiel Annaert

Blog and interview questions by Jared Piazza and Rebecca Gregson